Understanding the differences between consensus and consent is a crucial aspect of decision-making. It helps you make good decisions faster and more favourably!

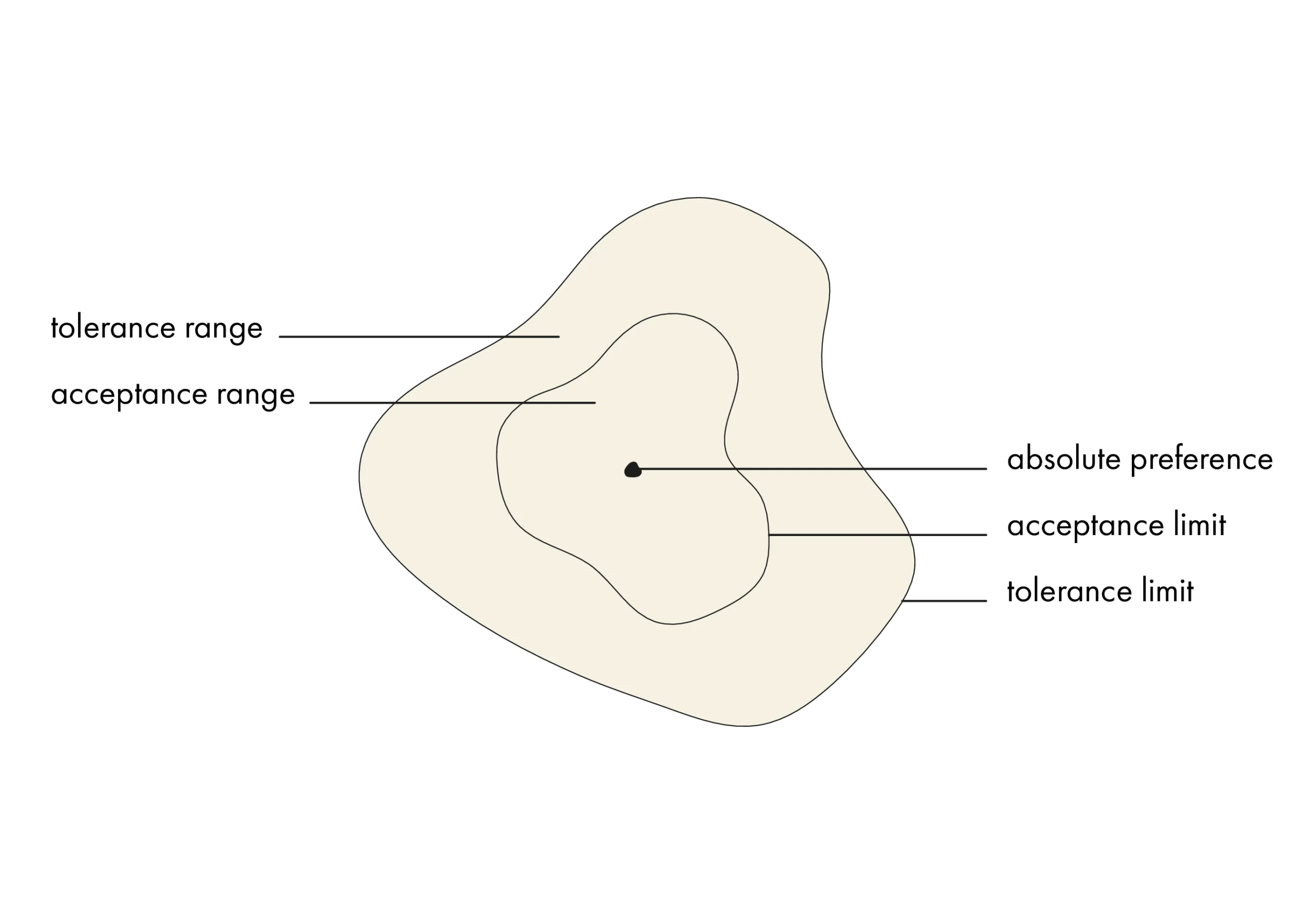

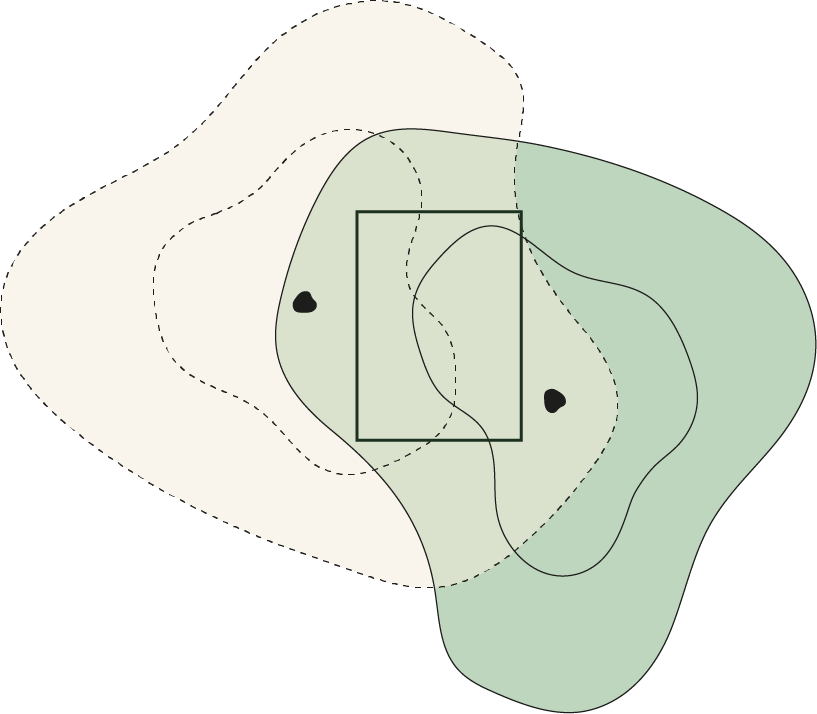

The individual preference spectrum

This diagram of a person’s preference spectrum shows how the terms acceptance/approval vs. tolerance/resistance relate to each other. The preference spectrum illustrates the extent of preference with regard to various aspects (e.g. spatial, temporal, monetary, etc.).

At the core is the absolute favourite alternative that perfectly combines all aspects. Within the acceptance range (consensus), approval for all other options continues to decrease until the point is reached at which an alternative is barely acceptable. This point is called the acceptance threshold. It is the point at which those involved perceive the alternative as ‘neither good or bad’ or ‘not effective with regard to the problem’. ‘According to Günther Drosdowski, acceptance means to accept, consent or acquiesce. He adds an active component to the word, while tolerance is interpreted more as passive acquiescence.’ [Wikipedia, 2023-1] If the acceptance threshold is exceeded, other alternatives are only tolerated. The resistance building up within the tolerance range (consent) continues to grow until it reaches a point where the alternative is no longer tolerable. At this point, the person raises a ‘serious objection’ and vetoes the decision.

Joint decision-making means agreement

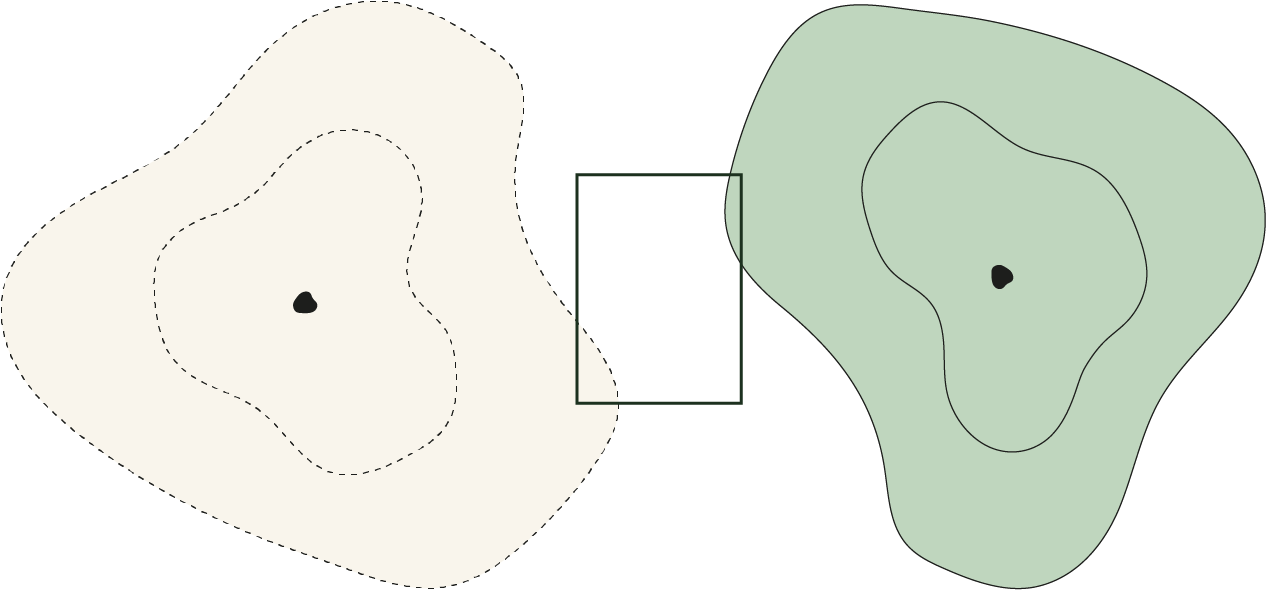

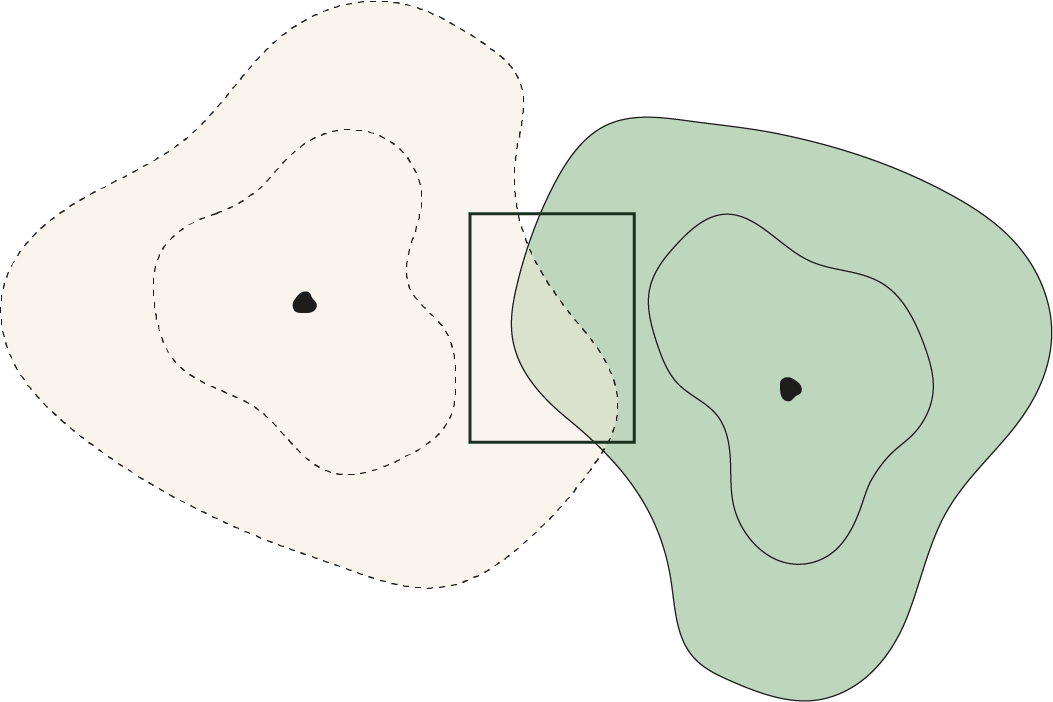

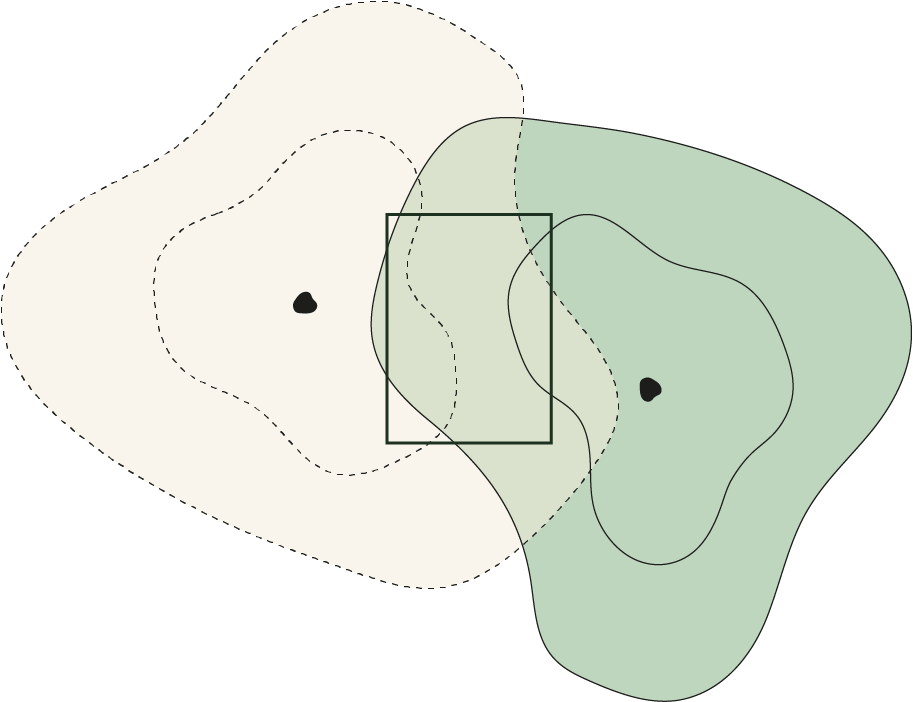

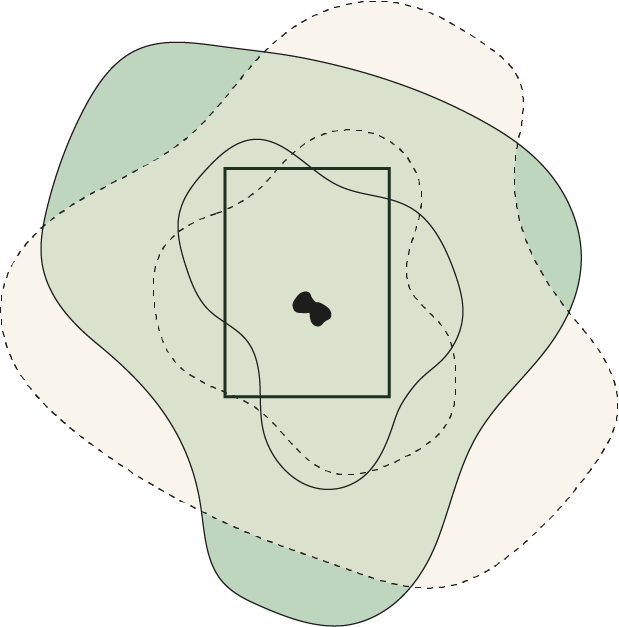

Below, we will see how this works for two people who are evaluating the solution space (the rectangle) in the decision-making process.

No agreement is possible here: the solution space only contains alternatives that are not tolerated by both people at the same time. Individual alternatives are still rated as tolerable by one person, but not by both at the same time. Each person will veto the alternative that the other can just barely tolerate.

Both can now ‘tolerate it’, ‘come to terms with it’. The solution space is completely or largely within their respective tolerance ranges, but neither of them really likes it all that much. The familiar term ‘lowest common denominator’, or basic consent, lies where the two tolerance ranges meet.

Now, there is already approval (acceptance) for individual alternatives. Each person has identified alternatives that they like. The common denominator of tolerance remains. We call it high consent.

Now, the acceptance ranges overlap, i.e. there are alternatives that all participants agree on. A (slight) agreement emerges: basic consensus. This is the prerequisite for jointly agreed, intrinsically motivated projects.

Now, the solution space is almost completely within the acceptance range of both people at the same time; the absolute preferences are close together. This is called ‘(overwhelming) agreement’ or high consensus – the ideal that everyone always strives for. It should have become clear why this is usually illusory – even with only two people…

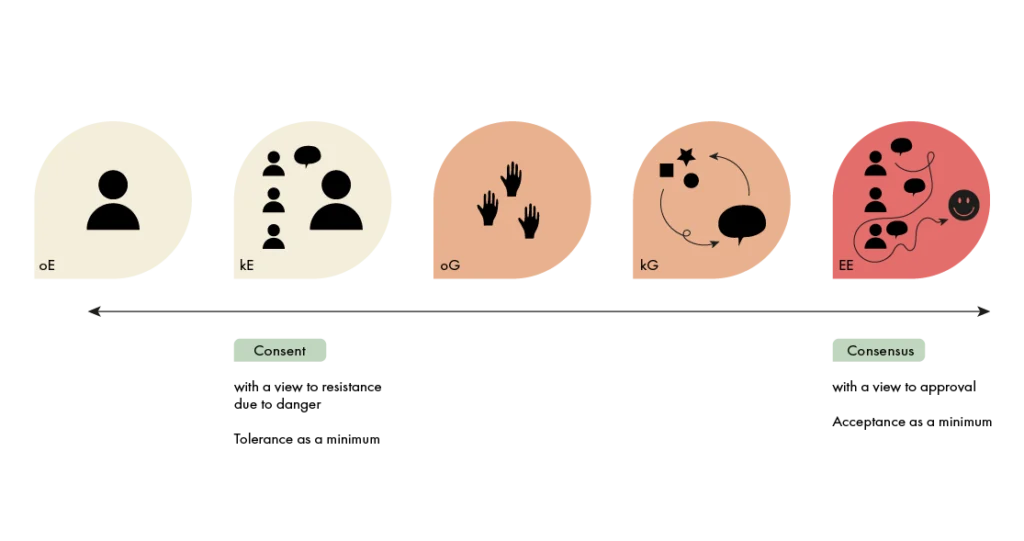

Mapping ask DAD’s methods

The individual decision

The ‘operative individual decision (OID)’ method often does not even strive for consent.

We make hundreds of decisions every day. Therefore, it would be a miracle if every other person expressed their approval for the alternatives we picked. Otherwise, there would only ever be one dish for lunch for everyone on the same day! In reality, however, there will always be many people who find my lunch intolerable, for example, due to food allergies. But that’s also the great advantage of the operative individual decision (OID): I determine the solution space solely based on my personal tolerance range and pick the alternative that comes closest to my preference. This does not necessarily mean it’s easy, as it depends on the object of the decision. This decision method is not the focus of ask DAD. You can find out more about the various methods within traditional decision theory here.

If an individual makes a decision, but under the condition that they must have consulted everyone who is affected by their decision and everyone who is familiar with the object of the decision beforehand, we refer to it as a ‘consultative individual decision (CID)’. It was introduced by the book ‘Reinventing Organisations’ by Frederic Laloux [Laloux, 2015] and is the standard method for operative decisions in organisational models based on the Teal concept. DAD calls it the ‘consultative individual decision (CID)’. The goal of this process is to achieve basic consent, as the tolerance ranges of the people that were consulted are usually considered. However, it is not uncommon for their input to be disregarded. If you want to use this procedure with our Solution Finder, you should definitely and explicitly point this out when you initiate the decision. For example, you can add the following sentence in the description: ‘I would like your opinion on the topic, but I reserve the right to decide otherwise.’ You can find out more here:

Group decisions

In group decisions, at least basic consent is expected, but we should actually aim for more. Everyone involved in the decision-making process can contribute and usually raise their (serious) objections.

However, in the ‘operative group decision (OGD)’, it is acceptable for the decision to lie outside the tolerance range of individuals. The goal here is therefore basic consent.

This can even happen in the ‘consultative group decision (CGD)’, but the aspiration is at least high consent, or even better basic consensus. This also depends on the specific evaluation procedure (see also voting procedure). But the same rule applies regardless of the selected procedure: the more people are involved, the more likely it is that someone will not want to tolerate the chosen alternative. And, since the objective of the CGD is to prevent this from happening, it might be helpful to select evaluation procedures that allow a single veto to prevent an alternative.

This is one of the distinguishing features between CGD and OGD.

This point is essential in the ‘unified decision (UD)’. The goal here is always to achieve a high consensus. This is actually no longer about a decision in which alternatives are evaluated and all ‘inferior’ ones are cut/sorted out. Instead, deliberation continues until an alternative is found that is acceptable to everyone. Obviously, this is the most lengthy and complex procedure, which is why it is generally only used for particularly important, critical decisions.

References

- [Laloux, 2015] Laloux, Frederic: ‘Reinventing Organisations’, Vahlen, 2015, ISBN 978-3-8006-4913-6

- [Wikipedia, 2023-1] Wikipedia: ‘Acceptance’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acceptance, retrieved in June 2023