The literature on voting procedures rarely examines the “process modalities” (sometimes also pejoratively referred to as “process formalities”), such as the type of communication in the proposal phase or the type of voting (classic: secret/anonymous voting). Mostly it is about the evaluation of the individual alternatives and the algorithm for evaluating the votes cast. An overview of this can be found on Wikipedia under the term “Electoral system”[Wikipedia2023-2] or “Electoral procedure”[Wikipedia2023-3].

Ranking procedure vs valuation procedure

First of all, a distinction can be made between majority voting, rank voting and score voting (note: in English, rank voting is called “rank voting” and score voting is called “range voting” or “score voting” – “range” in English is therefore a scoring method). This distinction is extremely important. There are reasons for this in terms of game theory, social science and mathematics. This is because Arrow’s impossibility theorem applies to majority and ranked voting procedures, which states that a joint decision cannot reasonably be reached if certain basic requirements are insisted upon. (See[Wikipedia-1:Properties] or also [Arrow1963]/[Wikipedia-4] and [BambergCoenenbergKrapp2019:216ff])

Unfortunately, this also applies to most electoral procedures in Western democracies. See[Wikipedia-4:Examples] and also[ElectionScience],[FairVote],[ElectoralReformSociety] and [Poundstone2008].

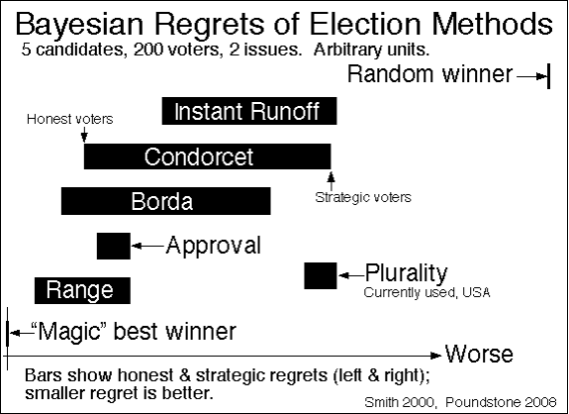

Warren D. Smith used Baysian Regrets to investigate how different voting procedures are perceived in relation to the result[SmithWeb:BayRegExec]. This image, which can also be found in Poundstone’s book [Poundstone2008], summarizes the results for a specific scenario:

You can clearly see that range voting performs best when voting is sincere (and not tactical). “Appoval” is the simplest of all evaluation procedures. “Borda”, “Condorcet” and “Instand Runoff” are ranking procedures. “Plurality” is majority voting; the simplest of the ranking procedures.

This basic problem can be summarized as follows: If a person is only allowed to choose one alternative (i.e. majority voting, which is common in democracies), they do not in fact give an assessment of the other alternatives. Majority voting is, so to speak, an extreme form of ranking procedures, because only the first rank is determined. Ranking procedures that allow all alternatives to be ranked say something about all alternatives because they have all been ranked, but it is neither clear how much the preferences differ nor where the pain threshold lies, so to speak. Do you like the alternative in second place only half as much as the one in first place or are they close behind? And: Does someone like an alternative that they chose third out of eight only less than the first two or not at all? Because the differences in approval/disapproval are not visible, the ranking methods are ordinal methods; they only measure ordinally. In the evaluation methods, on the other hand, the level of opposition or approval is explicitly stated for each alternative. The measurement is therefore cardinal.

DAD is primarily aimed at organizations that are free to choose their election procedures 😉

And DAD wants to do better.

For this reason, DAD uses the evaluation procedures explained below.

Resistance query

The method used as a quasi-standard in sociocracy is an evaluation method that looks exclusively at consensus and therefore only measures resistance. Several scales are possible here; two scales are common.

Scale for the classic systemic consensusT:

- 0 stands for “no resistance” (acceptance limit)

- -1 for “slight resistance” (i.e. within the tolerance range)

- -2 for “strong resistance” with the consequence of a “serious objection” or “veto” (see also KonsenS vs. KonsenT)

Scale for resistance assessment in systemic consensus building:

- from 0 to -10

- 0 again stands for the acceptance limit, i.e. “no resistance”

- The minus values represent the increasing resistance in the tolerance range

- In systemic consensus, there is typically no veto in the vote because the alternatives are eliminated beforehand in the proposal phase (i.e. “serious objections” are integrated there).

Once each participant has cast their vote, DAD calculates the average for each alternative and the alternatives are then sorted in descending order.

Vetoes

In sociocracy, it is customary to carry out the decision-making process synchronously, i.e. in real time in a meeting, and “serious objections” must be taken into account. Through this “integration of objections” directly in the meeting, new proposals are created and those with “serious objections” are no longer available for voting. This also applies to governance changes in Holacracy.

In an asynchronous process – as made possible by the Solution Finder of ask DAD – this must also be resolved through communication. This means that the objector must formulate this clearly in their comment. Ideally, the veto provider will already have drafted a new, “integrating” proposal. If this is done, the proposal threatened with veto can be deleted by the proposer during the proposal phase.

An individual veto must be viewed critically, as it can prevent change and presupposes that the group members making the decision understand all the alternatives to a sufficient extent and are therefore able to assess them at all and – see consensusS vs. consensusT – that at least their tolerance ranges all overlap, which is rarely the case for very large groups.

Full Range

This evaluation method actively distinguishes between the acceptance and tolerance range and includes the entire spectrum of opposition, abstention and approval. It measures the degree of approval (the preference differences in the acceptance range) and the degree of opposition (the preference differences in the tolerance range). Abstention corresponds to the acceptance threshold. In other words, the point at which an alternative is no longer really supported, but nothing speaks against it.

The active distinction between encouragement and resistance now offers the possibility of balancing between “suffering” (what one has to endure) and “satisfaction” (what one prefers).

Usually, more weight is given to avoiding suffering than to creating satisfaction. Resistance can therefore be weighted here. This factor represents a kind of exchange rate between the positive and negative ratings, which probably varies with the groups and topics. It should at least be greater than 1 in order to place resistance above approval. If it is too high, an individual veto is possible again.

References

- [Arrow1963] Arrow, Kenneth J.: Social Choice and Indivdiual Values, 1963, 2nd edition, Yale University Press

- [BambergCoenenbergKrapp2019] Bamberg, Günter; Coenenberg, Adolf G.; Krapp, Michael: Betriebswirtschaftliche Entscheidungslehre, 2019, 16th edition, Vahlen, ISBN 978-3-8006-5884-8

- [ElectionScience] Center for Election Science, USA: Website, https://electionscience.org/, accessed 06/2023

- [ElectoralReformSociety2023] The Electoral Reform Society, UK: Website, https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/, accessed 06/2023

- [FairVote] Center for Voting and Democracy, USA: Website, https://fairvote.org/, accessed 06/2023

- [Poundstone2008] Poundstone, William: Gaming The Vote – Why Elections Aren’t Fair (and what we can do about it), 2008, 1st edition, Hill and Wang, ISBN 978-0-8090-4893-9

- [SmithWeb] Smith, Warren D. et al.: Website, https://www.rangevoting.org/, accessed 06/2023

- [Wikipedia-1] Wikipedia: Evaluation procedure, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bewertungswahl, accessed 06/2023

- [Wikipedia-2] Wikipedia: Electoral system, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wahlsystem, accessed 06/2023

- [Wikipedia-3] Wikipedia: Election procedure, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kategorie:Wahlverfahren, accessed 06/2023

- [Wikipedia-4] Wikipedia: Arrow theorem, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrow-Theorem, accessed 06/2023